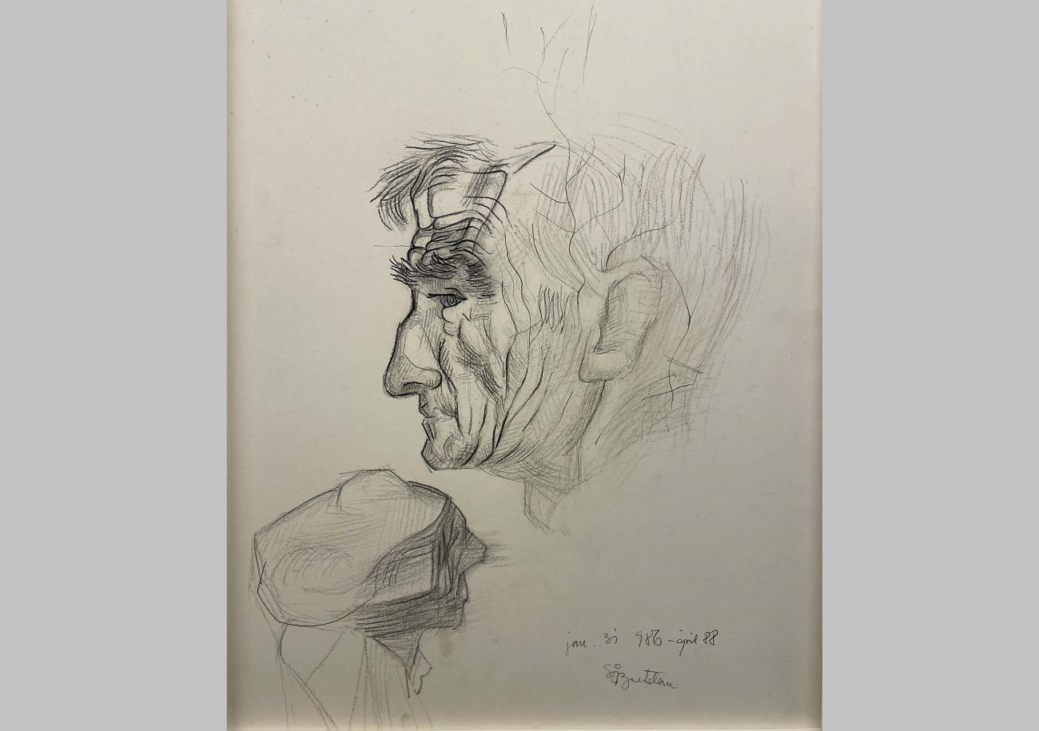

INTERVIEW – Bernard Blistène, about Ștefan Bertalan, the resilient Romanian artist and community builder

Bernard Blistène, curator and honorary director of the National Museum of Modern Art – Centre Pompidou Paris, talks in a curatorial interview about Ștefan Bertalan, the Romanian artist he discovered most recently, and about the exhibition he organized, the retrospective “In the Rhythm of the World”, at MARe/ Museum of Recent Art in Bucharest, which he wants to bring to France.

The “resilient community-building artist”, as Blistène calls Bertalan, was active from the 1960s until the end of his life in 2014.

Ecology, science, collaborations, collaborations, education, photography and performance are some of the elements that have marked and defined his creation.

“A knight of non-conformism”, as Prof. Eduard Pamfil noted, Ștefan Bertalan believed in what he did and left thousands of works and documents that speak about his solo creation, but also with the artistic groups 111 and Sigma, which he co-founded.

This is the first exhibition that Bernard Blistène is organizing in Bucharest, after presenting it last year in Timisoara. He has visited the capital before, 15 years ago, when he toured the country linked to one of his grandparents, who left Romania at the turn of the last century. Now it seems to him to be going “in the right direction”, that it has progressed, especially from a cultural and artistic point of view.

“Here, people are really involved in a collective experimentation, they share things, they know what to do and they are quite committed. It’s a huge step. The art scene, across the country for more than a century, has been spectacular. Of course, many have fled here and made careers abroad.” This is also the case for teacher and artist Stefan Bertalan. After a decades-long career in Timisoara, he left with his family for Germany, returning after 1990.

Bernard Blistène at the Museum of Recent Art

When and how did you discover Stefan Bertalan’s art?

Bernard Blistène: Quite late. One of my best friends whom I trust and with whom I have shared many things in my life introduced me to Ovidiu Șandor (collector, president of the Art Encounters Foundation, editor’s note). They told me about Bertalan five years ago. I didn’t know who he was. I saw some works and I knew more about Sigma, because the group was linked to France through the Hungarian artists Victor Vasarely and Nicolas Schöffer and through Roman Cotoșman, who went there and brought back information from Paris. I knew little about these things and a little more about kineticism, this early abstract dimension. Ovid told me about their work and I saw at one of the Art Encounters Biennials a work by Bertalan – a figure with open arms. I asked whose it was and that’s how I found out. Ovid asked me if I wanted to be involved in the retrospective of Bertalan’s work that he wanted to organize and I immediately accepted.

I went to Berlin, to the Esther Schipper Gallery, a rather large gallery that administers the artist’s legacy. I saw more than a thousand drawings and writings that were unclassified. I found it impressive.

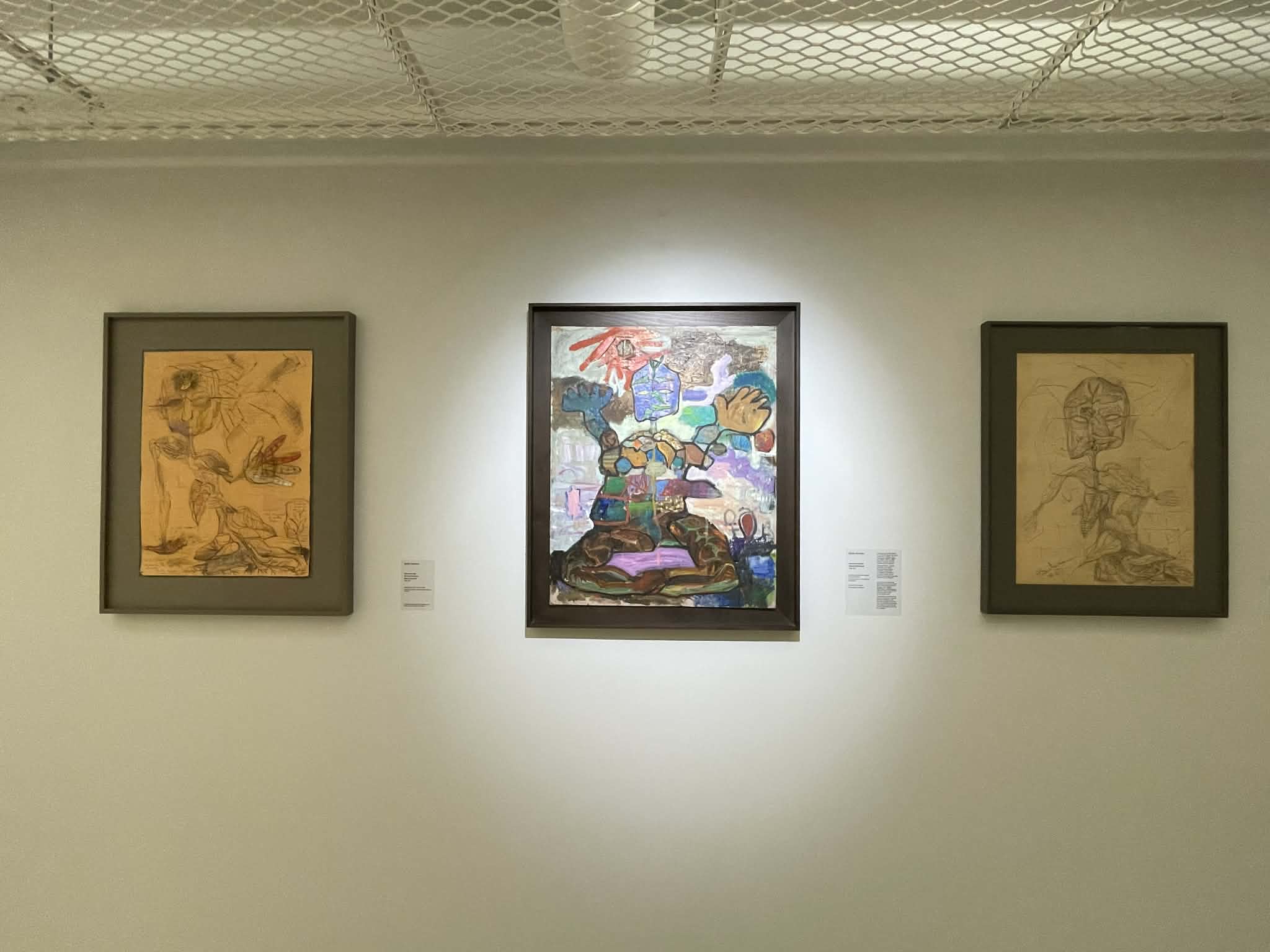

Artwork by Ștefan Bertalan; curatorial

What impressed you the most?

Bernard Blistène: Diversity, intensity, quality, uniqueness. He is an artist who developed his technique, his practice in an abstract manner. I didn’t know anything about his life, but of course I found out from books. I talked to specialists, friends of his. I remembered seeing an entire room with Bertalan at the 2013 Venice Biennale organized by Massimiliano Gioni. I’ve seen so many things in life that sometimes I feel disconnected. So I had to somehow reconnect what I saw. And I tried, yes, to propose a selection of works. I selected these works and as soon as I managed to put something in order, we set a date together and here we are today.

But my wish now is to take this exhibition to France.

When do you think this will happen?

Bernard Blistène: Let’s see. You know, with all this chaos in the world. We’re taking it one step at a time, but it’s definitely going to be.

How is the exhibition at MARe different from the one at ISHO Timisoara?

Bernard Blistène: Well, they are more or less the same works, except that we found out about multivision, which is the most important one in the early collective works at Sigma, which we couldn’t get in Timișoara because it was already included in this group show at the museum organized by Ileana Pintilie. As for the works, it’s the same and with the same number. Here we also have a room dedicated to Sigma – with archives, films, where there will be weekly, I think, dialogues by people who are connected with these things. Some of them have contributed texts to a 360-page book we’ve done on Bertalan.

Here, at MARe, we are in a labyrinth, compared to the space in Timișoara. It’s more theatrical. Of course, each exhibition is different.

It’s a double exploration.

Bernard Blistène: It is. I must say that I really like it here because the place is full of surprises.

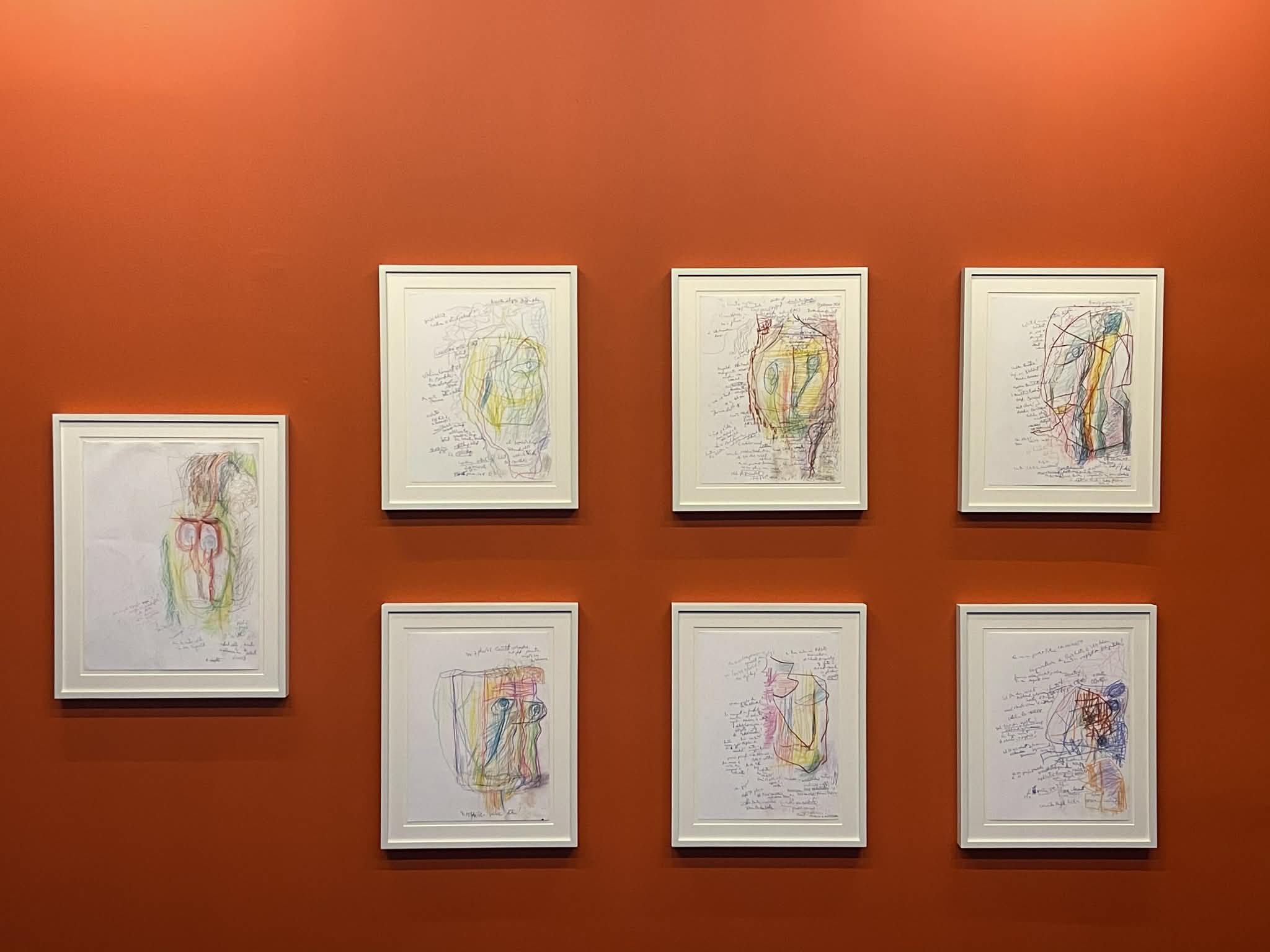

Drawings by Stefan Bertalan; curatorial

To what extent do you consider that Bertalan’s experience with his two experimental groups, 111 and Sigma, anticipates or dialogues with Western artistic practices of the 60s and 70s?

Bernard Blistène: That is the question. Most of the 111 and Sigma stuff happened in the late ’60s and early ’70s. In the international context, it seems to me that, if I’m not mistaken, this is the first step towards another recognition, which in some ways is quite important, because it is, politically speaking, a statement against this context. I’m not talking about the first avant-garde, I’m not talking about Brâncuși, Tzara, Brauner and many others, but I’m talking about what happened and how they resisted political pressure.

I remember that I was walking with Ovidiu Șandor in Timișoara when he explained to me that the 1989 revolution started there. And he explained to me how, from a political and philosophical point of view, Timișoara was a pretty powerful place. So, in a way, let’s say that what happened at the Polytechnic University and the fact that the works there, the visual works, were related to some scientists, writers, mathematicians and so on, this disciplinarity of the employees opened their minds and opened another dimension.

In your view, do the central themes and obsessions of Bertalan’s work remain relevant for contemporary audiences?

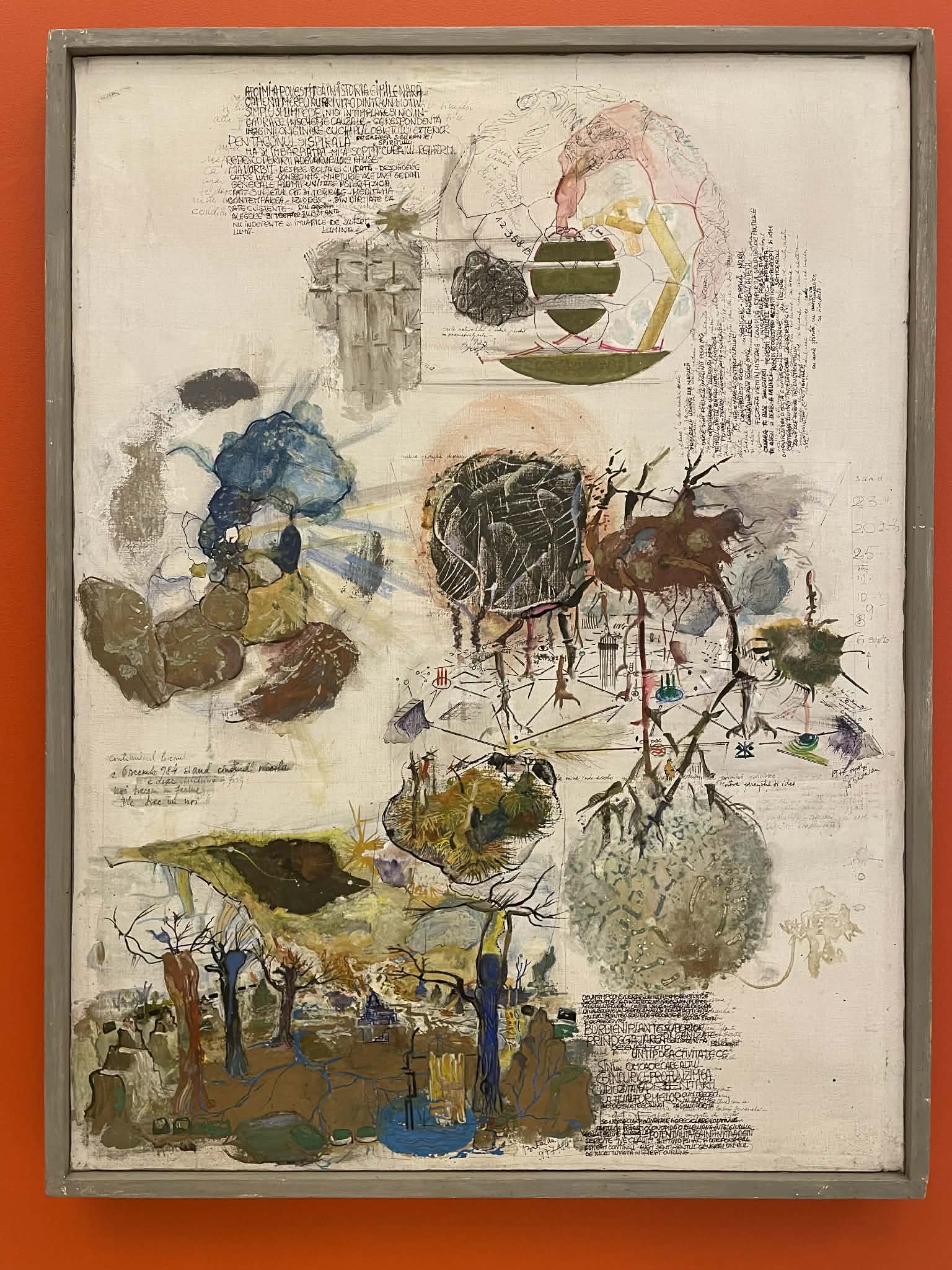

Bernard Blistène: Probably more than ever. The singularity, the ecology, the engagement with nature, the psychoanalysis, but also the technical diversity of what he was doing, the devices and all these things, probably make his work attractive, but they also make it quite diverse and experimental. The fact that he believed in experiment, in experimentation, and also the fact that he sort of created his own style, if I can put it that way, out of all of that.

Well, we know the late nights are closely tied to his illness. But somehow, to me, they’re absolutely spectacular. And you could compare them to many other informal things. Which is, in a way, sad. The fact that he was a great reader, and he didn’t like to talk about the past, but just to consider the fact that he loved an artist like Joseph Beuys. And I can imagine there were many others… as far as she could know them. If he had lived, say, in a moment of freedom, he would, of course, have been part of this familiar pattern, and my desire is certainly to bring him into it. To be part of this international network. That is the challenge. That’s why such a challenge must necessarily be taken abroad. Because nobody is a prophet in his own country, as they say.

He was a good teacher who believed in education and believed only in imparting knowledge inside an art school. He was an outsider at that time in the University, I think. It’s hard to be an outsider.

“Cauliflower”, Stefan Bertalan; curatorial

As a curator, how did you approach the relationship between the theoretical, almost scientific dimension of Bertalan’s works and their poetic or spiritual component?

Bernard Blistène: Well, I might have an answer or something like “science is poetry”. In a way. You know, all my friends who were involved in science tell me that everything always starts with something like an enlightenment. The greatest discoveries were always invented with a touch of imagination. So I don’t know if I would distinguish between what you call science and, on the other hand, the other works, especially given the fact that, if you look at most of the works, they are always a combination of the two. It represents research. Sometimes it reminds me of Beuys, who was a great artist who started out as a performer. I found out that Bertalan liked performance. He was quite physical and not just in the studio.

What do you think the European art scene in general can learn from the journey of an artist who created experimentally in a restrictive political context such as communist Romania?

Bernard Blistène: For example, the artist Victor Man was familiar with Bertalan’s art. He started working with a German dealer who I think introduced him to Bertalan’s work. So a Romanian artist from another generation had contact with an artist he liked facilitated by a German. This is important. I believe in this network, just like I believe in friendship, community… Community has to be rebuilt. Despite being a loner, Bertalan found his way and created two communities. Against any kind of nationalism, I believe in this artistic community, community of ideas.

Here’s a counter-example: I worked in Russia before what happened, before it became what it became. The artists I met wanted to develop different things outside the country and they could do that at that time. And this is where they are now.

The next exhibition I have, which is coming up soon in Paris, is with a Russian artist – Igor Shelkovsky, who is quite old, he’s 88. He decided to flee the country and settled in France. He saw that he couldn’t be an artist in that horrible system, so he turned to a friend of his, an art critic, who invited him to come and join the French community. And he became French.

There are many artists who have left their countries with oppressive systems to create elsewhere. I believe that an artist, by definition, is a citizen of the world.

Has to be.

Bernard Blistène: And it probably comes too late, but it always comes too late, but I think an artist like Bertalan should be a citizen of the world. In some ways he was. His recognition started abroad, in Germany, and then it reached France.

Besides, it is now a big challenge to take such work abroad, especially in such nationalistic times.

And because we were talking about communism, everything is closed now in Russia, in China, in Venezuela… but an artist has to escape. History repeats itself, but in a different context.

Main image: Self-portrait Stefan Bertalan, 1986 – 1988; curatorial